Why we need Dependable, not Radical, Candor.

Jun 15, 2021

Written by Richard Claydon | (cover image: @amyhirschi)

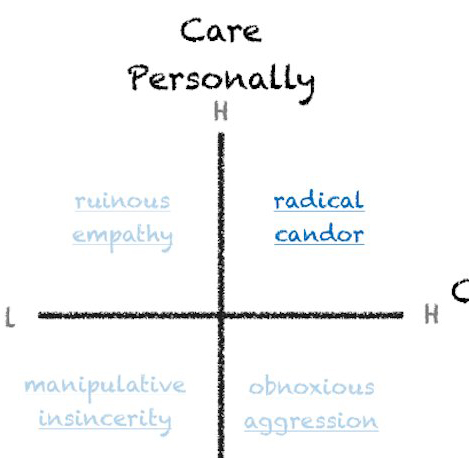

In her book, Radical Candor, Kim Scott presents a classic two-by-two matrix of management types.

She argues that great managers care personally and challenge directly, via radical candor. The alternatives are:

-

Manipulative insincerity: when praise is given not because it is genuine, but for another motive or agenda.

-

Obnoxious aggression: what it says on the tin

-

Ruinous empathy: being too nice, being afraid of being called a jerk (according to Scott, responsible for 85% of management mistakes)

Scott illustrates her moment of epiphany by detailing a conversation she had with Sheryl Sandberg, after Sandberg, then with Google, had watched Scott present to Google’s CEO and founders on the performance of the product she was leading. Although the presentation went well and Sandberg was full of praise for Scott’s knowledge, she suggested they take a walk at its conclusion. As they walked, it quickly became clear to Scott that something was wrong. After Sandberg reiterated how much of a success the presentation had been, this exchange followed.

Finally, she said. “You said ‘um’ a lot. Were you aware of it?”

“Yeah,” I replied. “I know I say that too much.” Surely she couldn’t be taking this little walk with me just to talk about the “um” thing. Who cared if I said “um” when I had a tiger by the tail?

“Was it because you were nervous? Would you like me to recommend a speech coach for you? Google will pay for it.”

“I didn’t feel nervous,” I said, making a brushing-off gesture with my hand as though I were shooing a bug away. “Just a verbal tic, I guess.”

“There’s no reason to let a small thing like a verbal tic trip you up.”

“I know.” I made another shoo-fly gesture with my hand.

Sheryl laughed. “When you do that thing with your hand, I feel like you’re ignoring what I’m telling you. I can see I am going to have to be really, really direct to get through to you. You are one of the smartest people I know, but saying ‘um’ so much makes you sound stupid.”

Now that got my attention.

Sheryl repeated her offer to help. “The good news is a speaking coach can really help with the ‘um’ thing. I know somebody who would be great. You can definitely fix this.”

This is, of course, great feedback. Within the Radically Candid environment Scott wishes us to create, it’s exactly what is required. Sheryl Sandberg knows it is something female executives have to focus on in the bro cultures of Silicon Valley, and possibly across the entire world of work. The advice would have been incredibly helpful.

But, but, but…

It’s impression management.

It is performing according to the audience’s expectations of what good looks like.

For somebody who has Sheryl Sandberg’s sponsorship, it can be corrected through public-speaking training paid for by Google’s deep trough of money. Scott can learn to perform according to the audience’s requirements, manage their impression of her, and be very successful. And she did.

Re-balancing the Dominant Leadership Discourse

But what about the people who don’t want to be an Apple manager? What if, like Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, they just want to be engineers who build or design great stuff and have no managerial responsibilities? Do they have to suffer a manager’s radically candid critiques of their performative displays? Do they have to learn to behave differently and end up feeling they are fakes? Do they have to continuously deal with the stress that accompanies such feelings and does this stress make them worry that they will lose their job?

Radical candor is irrevocably mixed into a very specific leadership discourse that stretches back to the 1930s, when leadership traits were first being scrutinised and identified. The leaders observed in this research were predominantly white, North American males. It is, therefore, unsurprising that the “natural” leadership traits identified in the research were the traits of alpha-males within a North American cultural context. In this discourse, a leader is:

-

Assertive

-

Self-Confident

Such leaders are confident they’re right and will have no problem asserting that rightness in presentations, meetings and feedback.

In Radical Candor, Scott adds a new twist to this discourse - the caring personally dimension. For Scott, Sandberg cared personally enough to take the time to have that difficult conversation. At this level, radical candour is the organisational form of tough love and a re-balancing of an overly masculine trait-set.

In essence, Scott has added a hyper-feminine balance to the hyper-masculine traits outlined above.

Sandberg’s advice to Scott helped her understand that she needed to convey the impression that she possessed certain traits, as by not doing so, she would be deemed as “stupid” by powerful audiences. They may not have been natural, but if she could perform in a way that suggested she had them, then over time she would fully develop them and make them part of her identity.

Scott’s work is a necessary balancing of the leadership discourse and something to be applauded. Nor is it surprising that it resulted in a higher performance from those in leadership or management roles. However, in terms of a high-performing, psychologically safe team, it doesn’t go far enough.

The Ivy League Performativity Problem

We need to go back to Google to examine why. When Sheryl Sandberg and Kim Scott were working at Google, the hiring policy focused on Ivy League students. Within Ivy League business schools, there is a very specific method of performing. Harvard Business School’s MBA Case Method is the most well known example. To succeed, students have to fight to be heard, vigorously striving to be the person the lecturer picks out to provide the answer. The extrovert, self-confident, assertive and articulate students are the ones who succeed.

Sheryl Sandberg, who was summa cum laude at Harvard College in her Bachelors of Economics degree, earned a High Distinction MBA from Harvard Business School and won a fellowship. She met Scott, who also has an MBA from Harvard, during those studies. When she graduated, she spent a year working for McKinsey, a Harvard dominated consulting firm.

These are amazing achievements for anyone but for a woman to have achieved them in such alpha-male environments is nothing short of outstanding. It will, however, have required excelling at a very specific type of performance. Sheryl Sandberg had to convey the impression that she was better than the men at their own alpha-male game.

The knock on from such an educational experience is displayed in Sandberg’s advice to Scott. Be self-confident and assertive in your speaking. Take that hyper-self-confident, assertive role. Show people you are serious.

There is a problem with the Harvard model, however. It assumes that a certain type of performativity correlates with excellence in actuality. Style is confused with the substance. While not wanting to denigrate those who have graduated from Harvard, or suggest for a second they don’t possess first-class intellects, we need to look at the reason Google no longer hires exclusively from Ivy League schools.

In 2015, Laszlo Bock, Vice President of People Operations at Google from 2006 - 2016, and author of Work Rules, a deep dive into Google’s recruitment and cultural policies, stated that:

It's one of the flaws in how we assess people. We assume that if you went to Harvard, Stanford or MIT that you are smart. We assume that if you got good grades you will do well at work... There is no relationship between where you went to school and how you did five, 10, 15 years into your career. So, we stopped looking at it.

Bock explained that, instead, Google was taking psychological safety more seriously, saying that “the safer team members feel with one another, the more likely they are to admit mistakes, to partner, and to take on new roles.”

None of that can happen in a Harvard / Ivy League environment in which the impression conveyed by a certain type of performance is the key to looking good and being seen as leadership material. If everybody is fighting like alpha-dogs over scraps of meat, then psychological safety will disintegrate fast.

Towards Dependable Candor

As a direct result of the insights into psychological safety from Project Aristotle, Google changed its hiring policy and looked for people who, when confronted with a complex problem, were willing to step in and help but equally willing to step back and let somebody else take over. Google wanted people who could give up power, who would allow other ideas space to flourish, who were able to admit to mistakes or accept that they were wrong, and who were likely to come up with ideas that were different to the norm.

To achieve this it had to remove or at least dilute those people whose assumption of the rights of leadership were drowning out other voices with their assertiveness and aggression.

Radical candor doesn’t work well in terms of psychological safety in teams because it is based on the performance of somebody in a position of authority who tells a subordinate how to improve. So while it adds some much needed femininity to the leadership discourse, it is still underpinned by an extrovert, assertive, self-confident, drive for achievement discourse that disables other more introverted, modest, reserved and collaborative voices.

Those who aren’t extroverted, assertive and self-confident, and who don’t want power and achievement, still have things of worth to say. Their personality doesn’t stop them having potentially game-changing ideas. The worry for any organisation in today’s digitally transforming landscape should be that such ideas aren’t heard. If one person in a company can have them, then it’s certain that people in other companies are having them too. Disruptive ideas change markets, as Kodak, Nokia and Blockbusters have found out to their cost.

As organisational leaders it is vital that we can depend on ideas being aired, and it’s just as vital that problems are spotted before they escalate to scandalous levels. Questions about decisions that might have terrible ripple effects must be asked, and a deep compliance with the company’s conventional ways of thinking and doing needs neutralising before it kills innovative and entrepreneurial possibilities.

As such, candour in teams and companies can’t just be radical. It must be dependable.

Dependable Candour: A Six-Point Guide

-

We create our world through reflection and action

-

We actualise everyone’s potential to our best ability

-

We don’t judge the person, we critique the idea

-

We ask questions, admit mistakes, offer ideas and think differently

-

We are an interdependent sensor system

-

We are an interdependent solutions system

1: We create our world through reflection and action: Every action must be a thoughtful one and we must think about its efficacy while we are doing it. There are three elements to this:

-

Will the action result in the team getting closer to its goal? Is it efficient and effective?

-

Will the action cause unnecessary suffering to others in the team or organisation? By choosing this method will we make their lives worse and, despite getting closer to our own goals, hinder others (and the organisation as a whole) from achieving theirs?

-

Is there another action we can take that might be more efficient and effective as well as less harmful to others and to the organisation? Might this method be game-changing?

2: We actualise everyone’s potential to the best of our ability:

Not everyone has to fit a culture or display traditional leadership qualities to have value so don’t try to force people into these boxes. Instead, encourage them to display their talents in a way that makes sense to them, not you. Help them grow into a shape that is useful to them, to you, and to the organisation.

3: We don’t judge the person - we critique the idea: In Originals, Adam Grant argues that the difference between a person who has a lot of ideas and a person who doesn’t is simple. When the person with a lot of ideas starts to perceive a particular idea as foolish or flawed, they try to work through the complexities,only abandoning it if the flaws prove insurmountable. When those who don’t have so many ideas see that their own idea is foolish or flawed, however, they take another step. They think they are also foolish and flawed. They internalise this and because they don’t want to feel so vulnerable and self-critical again, they resist having new ideas.

The team’s job is to make everyone feel great about having ideas, even flawed ones. If they don’t then the potential for the best idea ever might be lost.

4: We ask questions, admit mistakes, offer ideas & think differently:

These are the core observable behaviours of psychologically safe environments

5: We are an interdependent sensor system:

As Amy Edmondson says, we are operating in an environment of uncertainty and interdependence. In any new situation we can’t know what will happen, nor can we know who might see a problem or provide a solution. It could be anyone in the team. We have to depend on everyone to sensemake at all times.

6: We are an interdependent solutions system:

We need everybody’s brains and voices in the game. Complex problems are not solved by individuals, nor by the person in a position of authority making all the decisions. Leadership must flow through the team so that any member can take up its mantle at some point in the problem-solving process. If that interdependence is enabled, then unexpected and innovative possibilities will emerge.